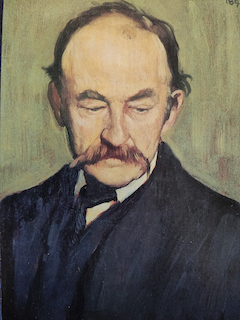

Most people know of Thomas Hardy as the author of the novels, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Jude the Obscure and others, set in the semi- imaginary countryside of “Wessex” . He is much less well-known as a poet. Indeed, until 1898, it was entirely to the novels that Hardy owed his contemporary fame as a leading Victorian literary figure. In that year he published Wessex Poems. Over the next 30 years, until his death in 1928, he produced a further seven volumes containing most of the 900 or so poems which he had penned.

Given such a prolific output, it is no surprise to discover that some of the poems refer to bells. But these are not the work of a writer whose only contact with bells was the distant sound emerging from some parish church. Hardy was almost certainly not a ringer himself, yet in his poems he displays a degree of knowledge about bells and ringing that suggests he could have been. Part of the explanation for this was Hardy’s early training and practice as an architect, which certainly brought him into contact with churches, bells and their ringers.

Drawing Details In An Old Church

I hear the bell-rope sawing

And the oil-less axle grind

As I sit alone here drawing

What some Gothic brain designed.

And I catch the toll that follows

From the lagging bell

Ere it spreads to hills and hollows

Where people dwell.

I ask not whom it tolls for

Incurious who he be

So, some morrow, when those knolls for

One unguessed, sound out for me.

A stranger loitering under,

In nave or choir,

May think, too, “Whose I wonder?”

But not inquire.

(Late Lyrics and Earlier 1922)

Thomas Hardy was born in Higher Bockhampton, Dorset on 2nd June 1840. His father was a stonemason, and musican at nearby Stinsford church. In 1856 Hardy began an architectural apprenticeship with Hicks of Dorchester and worked on several church restorations.

In 1862 he moved to London and acquired a position in the office of Arthur (later Sir Arthur) Blomfield. He stayed in London for five years before poor health forced him to return to Dorset and his previous post. Hicks’ practice had by then passed into other hand and it was his successor, Crickmay, who, in 1870, sent Hardy to St, Juliot in Cornwall to make drawings and advise on a restoration. His experiences there formed part of the inspiration for the poem above. When he arrived, he found the church of St Juliot in the sorry state described in Polsue’s Parochial History of Cornwall:

“Excepting the south aisle, extreme age has reduced this once superior church to a state of irremediable dilapidation: it is now, 1868, closed for reconstruction.The tower is in a ruinous and falling state. It contained five good bells but these have latterly been removed to the north transept for preservation.”

However, the bells had obviously not been in this position for too long. In her Recollections, Emma Gifford, the sister of the elderly rector’s second wife, records that:

“. . . when we arrived at the Rectory there was a great gathering and welcome from the parishioners, and a tremendous fusillade of salutes, cheering and bell ringing – quite a hubbub to welcome the Rector home with his new wife.”

The arrival of the new rector followed the institution of a proper living at St. Juliot, which had suffered from a succession of non-resident curates, as was witnessed by the physical condition of the church. Hardy spent March 8th 1870, his second day there, drawing the results of this neglect. His diary records:

“Austere grey view of hills from bedroom window. A funeral. Man tolled the bell (which stood inverted on the ground in the neglected transept) by lifting the clapper and letting it fall against the side. Five bells stood thus in a row (having been taken down from the cracked tower for safety).”

Hardy returned to St. Juliot two or three times a year while the restoration went ahead and in September 1874 he married Emma Gifford. The fictionalised story of their courtship was told in his novel A Pair of Blue Eyes, published a year earlier. After living in Yeovil, Sturminster Newton, London and Wimborne the couple settled in 1885 at Max Gate, the house Hardy designed and had built in Fordington on the outskirts of Dorchester. By this time his novels had brought him fame as a writer and he had ceased to practice architecture as a living, though his interest remained. His concern with bells had also developed.

Inscriptions For A Peal of Eight Bells After a Restoration

I Thomas Tremble new-made me

Eighteen hundred and fifty-three

Why he did I fail to see.

II I was well-toned by William Brine

Seventeen hundred and twenty-nine

Now recast, I weakly whine!

III Fifteen hundred used to be

My date, but since they melted me

’Tis only eighteen fifty-three

IV Henry Hopkins got me made

And I summon folk as bade

Not to much purpose, I’m afraid!

V I, likewise, for I bang and bid

In commoner metal than I did

Some of me being stolen and hid.

VI I, too, since in a mould they flung me

Drained my silver, and rehung me

So that in tin-like tones I tongue me

VII In nineteen hundred, so ’tis said,

They cut my canon off my head

And made me look scalped, scraped and dead.

VIII I’m the peal’s tenor still, but rue it!

Once it took two to swing me through it.

Now I’m rehung, one dolt can do it.

(Human Shows 1925)

This poem was probably written sometime between 1920 and 1924. But it is clear that, in thus putting bellfounders (and tenor ringers) in their place. Hardy was drawing on a variety of earlier personal experiences. I have been unable to discover whether he had a particular restoration in mind. He certainly knew about the work on the bells of St Peter’s, Dorchester in 1889 when the fourth, sixth and seventh were recast and the whole peal rehung by Warners at a cost of £300.

Whatever the precise inspiration, the poem itself reflects accurately Hardy’s strong feelings on the subject of restorations. In 1906 he submitted a paper, entitled Memories of Church Restoration, which was read to the Twenty-Ninth General Meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. The paper was subsequently published in the Society’s Annual Report. In it Hardy recounts one or two incidents from his early architectural work and then continues:

“My knowledge at first hand of church repair at the present moment is very limited. But one or two prevalent abuses have come by accident under my notice. The first concerns the re-hanging of church bells. A barbarous practice is, I believe, very general, that of cutting off the cannon of each bell – namely, the loop on the crown by which it has been strapped to the stock – and restrapping it by means of holes cut through the crown itself. The mutilation is sanctioned on the ground that, by so fixing it, the centre of the bell’s gravity is brought nearer to the axis on which it swings, with advantage and ease to the ringing. I do not question the truth of this; but the resources of mechanics are not so exhausted but that the same result may be obtained by leaving the bell unmutilated and increasing the camber of the stock, which for that matter might be so great as nearly to reach a right angle. I was recently passing through a churchyard where I saw standing on the grass a peal of bells just taken down from the adjacent tower and subjected to this treatment. A sight more piteous than that presented by these fine bells, standing disfigured in a row in the sunshine, like cropped criminals in the pillory, as it were ashamed of their degradation, I have never witnessed among inanimate things.”

Hardy returned to the subject of bell restoration in 1909 after reading the architect’s report on proposed work at Stinsford church. This was the church where Hardy senior had played the violin and which Thomas junior had immortalised in his novels as ‘Mellstock’. It was a place that was very close to his heart and, indeed, is where his heart is now buried. He submitted his Notes on Stinsford Church to the church restoration committee on 25th April.

“There are three bells in the tower – the first bell, cracked by being hammered at a wedding, should be recast if cutting out will not suffice. Care should be taken to employ a respectable founder, that base metal may not be substituted for the old, which is of high quality. If the other bells are rehung the cannons should on no account be cut off, as is the modern reprehensible practice, which can be avoided by giving more camber to the stock.”

He gave similar advice to A.M. Broadly, churchwarden of Holy Trinity, Bradpole, in a footnote to a letter dated New Year’s Eve 1909. This time attributing to the founders a less than charitable motive for such “mutilations”.

“PS. If you are going to rehang the church bells insist that the “cannons” shall not be cut off by the bellfounders on the plea of making the bells swing better The finest bells in England have been mutilated in that way of late years: and it is not at all necessary. Of course, the piece cut off goes into the founder’s melting-pot.”

With or without Hardy’s advice the work at Bradpole went ahead and was finished in time for the first peal to be rung in March 1910. The work at Stinsford took rather longer. The parish was having considerable difficulty in raising the funds to carry out work on the ring of three. It was not until 26th February 1926 that Hardy wrote to the vicar, Henry Cowley:

“In respect of the report by the bellfounders on the Stinsford bells I am thinking you might reply with some queries on these points:-

1. As the parish is not a rich one, could the difficulty and expense of re-casting the treble be got over by cutting out the crack, as was done, I believe with “Big Ben”? Even if the tone thus recovered should not be inferior to that of a new bell, there would be the great advantage of retaining the actual old bell, which is of pre-Reformation date.

2. Could not some of the oak from the old beams and bell-carriages be re-used, as it can scarcely be entirely decayed?

3. It is understood that, in re-hanging, the cannons need not be cut off from the heads of the bells, which would be fastened to the headstocks in the old manner. As they would not be rehung for ringing peals, there would be no object in mutilating them in the modern fashion to make them swing more easily.

I did not know that the old bells had such historic interest till I read the report, and if anything should be done I will subscribe something. I wish I could afford to pay for the whole job. The report is returned here with.”

The estimated cost of the job was £123 and Hardy wrote again the next day in response to a request from Cowley that he pen a few lines supporting an appeal for the money.

“I have been thinking over your suggestion that some thing could be done to raise subscriptions for the bells by a paragraph or so in the English and American papers to the effect that Stinsford is the church I have described under the name of Mellstock (it is not exactly so in trifling details, but never mind that). As I cannot very well draw attention to my own writings personally, all I can do is to furnish you with the facts enclosed, that you may make use of them in any way you choose with the above object. I hope it will be with some effect.”

“Mellstock Church” in Thomas Hardy’s novel Under the Greenwood Tree is well-known locally to be Stinsford Church under a very thin disguise. The sub-title of the story is “The Mellstock Quire”, the description of which, as it used to be before the substitution of an organ for stringed instruments, fills a large part of the book. The old west gallery, which also appears in the story, was removed when the old quire was abolished in the latter part of the last century. Several of Mr Hardy’s poems also refer to the same church and churchyard . . . . It is for the bells of this interesting Church that the appeal is made. They are in wretched condition, and the old oak bell-carriages and mechanism quite decayed. The tenor if of very fine tone, and the treble, which is cracked, is of pre-Reformation date [Any details from the Report that may be necessary can be added].”

By April Cowley had put together a quite differently worded appeal which he submitted to Hardy for approval. Hardy did approve and “hoped something would result”. The appeal appeared eventually in the Paris edition of the New York Herald for 25th April. It must have been the least successful piece of writing that Hardy ever undertook, for, in October, the Stinsford PCC issued a printed statement reporting that not a single contribution had resulted from the appeal. Nevertheless, by the end of 1927 the money was somehow found, the treble recast, and the bells rehung.

Hardy’s complaint about the removal of cannons was not the only one he made in his paper to the SPAB in 1906.

“Speaking of bells. I should like to ask cursorily why the old sets of chimes have been removed from nearly all our country churches. The midnight wayfarer, in passing along the sleeping village or town, was cheered by the outburst of a stumbling tune, which possessed the added charm of being probably heeded by no ear but his own. Or when lying awake in sickness, the denizen would catch the same notes, persuading him that all was right with the world. But one may go half across England and hear no chimes at midnight now.”

The chimes of St Peter’s, Dorchester played the Sicilian Mariner’s Hymn and Hardy referred to them in The Mayor of Casterbridge. They may also have been victims of the 1889 restoration, for he noted in a footnote to the poem After the Fair written in 1902 that “The chimes will be listened for in vain here at midnight now, having been abolished some years ago.” Once again, though, it was memory of these events recalled some years later that provided Hardy with inspiration.

The Chimes

That morning when I trod the town

The twitching chimes of long renown

Played out to me

The sweet Sicilian sailor’s tune

And I knew not if late or soon

My day would be.

A day of sunshine beryl-bright

and windless; yea. think as I might,

I could not say

Even to within year’s measure, when

One would be at my side who then

Was far away.

When hard utilitarian times

Had stilled Saint-Peter’schimes

I learnt to see

That bale may spring where blisses are

And one desired might be afar

Though near to me.

(Moments of Vision 1917)

This poem is about more than the loss of well-loved chimes. On 27th November 1912 Hardy’s wife, Emma, had died after a long and painful illness. This came as a great shock to him, though the two had steadily been growing apart for years and it was reputed that the new century had seen Hardy involved with a steady stream of literary ladies. Indeed, within a few months he had installed one of them, Florence Dugdale, at Max Gate; marrying her at Enfield Parish Church in February 1914. Nevertheless, Emma dead proved a much greater inspiration to Hardy than Emma alive had ever done. In the year’s immediately after her death he wrote more than fifty poems to her memory, many of them amongst his finest work.

End of the Year 1912

You were here at his young beginning

You are not here at his aged end

Off he coaxed you from Life’s mad spinning

Lest you should see his form extend Shivering, sighing

Slowly dying

And a tear on him expend

So it comes that we stand lonely

In the star-lit avenue

Dropping broken lipwords only

For we hear no songs from you

Such as flew here

For the new year

Once, while six bells swung thereto

(Late Lyrics and Earlier 1922)

Emma had been a regular attender at St George’s, Fordington and the Hardys could often hear the ring of six from Max Gate. In particular, listening for the bells on New Year’s Eve seems to have been a feature of the household’s ritual, both before and after Emma’s death. Hardy’s diary attested to this.

“New Year’s Eve1890 Looked out of doors just before twelve. I could not hear the church bells.”

“Dec 31st 1910 – Went to bed at eleven. East wind. No bells heard”

“Dec 31st 1923 – New Year’s Eve. Did not sit up. Heard the bells in the evening”

By 1914 the First World War had temporarily put paid to much ringing. In 1919, however, James Milner, editor of the Graphic, asked Hardy for a contribution to the Jubilee Christmas Number. Despite plenty of advance notice. Hardy was not optimistic. In June he wrote:

“I fear I cannot do anything for the Jubilee number since, as you know. I write very little now; nor on searching can I find anything that would suit. But if I come across anything in the course of the next few days I will send it. However, as I say. I fear not.”

On Thursday 30th October Hardy received the inspiration he needed to fulfil Milner’s request. It was supplied to him by a band of ringers from the Salisbury Diocesan Association who, on that day, rang the first peal at St Peter’s, Dorchester since 1913. It appeared in the Ringing World for 7th November which records that Holt’s Ten Part peal of Grandsire Triples was rung in 3 hours 14 minutes, conducted by Charles Goodenough. The footnote to the peal stated that:

“This peal, rung with hall-muffled clappers, was a memorial to those men of the Salisbury Diocesan Guild who gave their lives in the late war.”

Messrs Goodenough and Forfitt of Bournemouth, Uphill of Fordington, Jennings of Wyke Regis, Townsend of Poole, Beams of Bradpole, Stewart of Wimborne and Benger of Dorchester would not doubt have been surprised to learn that they were directly responsible for…

The Peace Peal

(After Four Years of Silence)

Said a wistful daw in Saint Peter’s tower

High above Casterbridge slates and tiles

‘Why do the walls of my Gothic bower

Shiver and shrill out sounds for miles?

This gray old rubble

Has scorned such din

Since I knew trouble

And joy herein

How still did abide them

These bells now swung

While our nest beside them

Securely clung…

It means some snare

For our feet or wings

But I’ll be ware

Of such baleful things!’

And forth he flew from his louvred niche

To take up life in a damp dark ditch

– So mortal motives are misread

And false designs attributed

In upper spheres of straws and sticks

Or lower, of pens and politics

At the end of the war (The Graphic 24 November 1919 and Human Shows 1919)

But it was a band of ringers several decades earlier who had provided the inspiration for what is, in some ways, Hardy’s most interesting bell poem. Again, it was written as the result of a request for a contribution to a Special Christmas Number for 1925. This time the magazine was the “Sphere”. The editor, Clement Shorter, obviously knew his man for he made his request almost a year in advance. Hardy replied in January 1925:

“Many thanks for New Year wishes I reciprocate. I will bear in mind the kind of poem you want and will try to let you have it soon. I think the price you offer very fair….”

The poem No Bell-Ringing – A Ballard of Durnover appeared in the Sphere on 23rd November 1925. It is possible to see in it the influence of a number of experiences from Hardy’s earlier life. In particular, a visit to a ringing chamber, a ghostly experience, a family tale and an architectural anecdote.

The visit to the ringing room of St Peter’s, Dorchester occurred on New Year’s Eve 1884 and was recorded in Hardy’s diary:

“To St. Peter’s belfry to the New Year’s Eve ringing. The night wind whiffed in through the louvres as the men prepared the mufflers with tar-twine and pieces of horse cloth. Climbed over the bells to fix the mufflers. I climbed with them and looked into the tenor bell: it is worn into a bright pit where the clapper is battered with its many blows.

The ringers now put their coats and waistcoats and hats upon the chimes and clock and stand to. Old John is fragile, as if the bell would pull him up rather than he pull the rope down, his neck being withered and white as his neckcloth. But his manner is severe as he says “Tenor out?” One of the two tenor men gently eases the bell forward – that fine old E flat, my father’s admiration, unsurpassed in metal all the world over – and answers “Tenor’s out”. Then old John tells them to “ Go!” and they start. Through long practice he rings with the least possible movement of his body, though the youngest ringers – strong dark-haired men with ruddy faces – soon perspire with their exertions. The red, green and white sallies bolt up through the holes like rats between the huge beams overhead .

The grey stones of the fifteenth century masonry have many of their joints mortarless, and are carved with many initials and dates. On the sill of one louvred window stands a great pewter pot with a hinged cover and engraved: “ For the use of the ringers 16-.” [now in the County museum]”

The ghostly experience takes us back to an even earlier period: to 1852 when Hardy was twelve. He was returning home at three in the morning with his father who had been playing the violin at a gentlemen-farmer’s. It was a snowy, frosty, moonlit night and they saw what they thought was a white human figure, without a head, motionless in a hedge. On closer inspection it turned out to be drunk wearing a white smock and in danger of dying from exposure.

Drink and a ghost also play leading roles in the family tale which was recorded in 1935 when the Women’s Institute encouraged their Dorset members to contribute to a local history competition. Clerk Hardy who takes centre stage in the following story was also named Thomas. He was flour- ishing in Dorchester from 1724 onwards and was claimed by our Thomas Hardy as an ancestor.

“Here is a story of St. Peter’s, Dorchester in 1814. It was Christmas Eve. The clerk and the sexton were in the church to decorate for the Christmas service on the following day, as was the custom … Clerk Hardy and Sexton Ambrose Hunt had locked themselves in, and were at length cold and tired. They sat down on a settle (now in the vestry) and from there they could see right down the north aisle of the church. Suddenly a most unlucky thought assailed their minds – the Holy Communion Wine was easy to come by. They seem to have offered little or no resistance to the temptation, and the wine was procured, but hardly had they taken the first sip than they became aware of a figure sitting between them, that of their late rector, the Rev. Nathaniel Templeman. They said he seemed to rise up suddenly; he looked at them with a very angry countenance and shook his head at them just as he did in life when displeased. Then rising and facing them he slowly floated up the north aisle and sank out of their sight. Clerk Hardy swooned, and the sexton tried to say the Lord’s Prayer. They were both very frightened, but stuck to their story. They said they could not mistake their old master, looking as he did in life and wearing the same clothes.”

The architectural anecdote takes us once again to Hardy’s paper for the SPAB in which he recounts this experience:

“I may here mention a singular incident which occurred in respect of a new peal of bells at a church whose rebuilding I was privy to, which occurred on the opening day many years ago. It being a popular and fashionable occasion, the church was packed with its congregation long before the bells rang out for service. When the ringers seized the ropes, a noise more deafening than thunder resounded from the tower in the ears of the startled sitters. Terrified at the idea that the tower was falling they rushed out at the door, ringers included, into the arms of the astonished bishop and clergy advancing in procession up the churchyard path, some of the ladies in a fainting state. When calmness was restored by the sight of the tower standing unmoved as usual, it was discovered that the six bells had been placed “in stay” – that is, in an inverted position ready for the ringing, but in the hurry of preparation the clappers had been laid inside though not fastened on, and at the first swing of the bells they had fallen out upon the belfry floor”

So there we have four strands; authentic ringing, a white figure, religious transgression and silent bells. Some of them it is difficult to take at face value but the link between them is what Hardy made of them in the following poem. (Incidentally, ‘Durnover’ is Hardy’s Wessex name for Fordington, and the Hit or Miss: Luck’s All’ was a local tavern, now demolished.)

No Bell-Ringing

A Ballad of Durnover

The little boy legged on through the dark

To hear the New Year’s ringing.

The three-mile road was empty, stark

No sound or echo bringing.

When he got to the tall church tower

Standing upon the hill.

Although it was hard on the midnight hour

The place was, as elsewhere, still.

Except that the flag-staff rope, betossed

By blasts from the nor-east,

Like a deadman’s bones on a gibbet-post

Tugged as to be released.

‘Why is there no ringing tonight?’

Said the boy to a moveless one

On a tombstone where the moon struck white.

But he got answer none.

‘No ringing in of New Year’s Day’

He mused as he dragged back home

And wondered till his head was gray

Why the bells that night were dumb.

And often thought of the snowy shape

That sat on the moonlit stone,

Nor spoke, nor moved and in mien and drape

Seemed like a sprite thereon

And then he met one left of the band

That had treble-bobbed when young

And said ‘I never could understand

Why, that night, no bells rung’

‘True there’d not happened such a thing.

For half a century; aye

And never I’ve told why they did not ring

From that time till today.

Through the week at the Hit or Miss

We had drunk – not a penny left.

What then we did – well now ’tis hid

But better we’d stooped to theft!

Yet since no other remains who can

And few more years are mine,

I may tell said the cramped old man

“We swilled the Sacrament wine.

Then each set to with the strength of two,

Every man to his bell.

But something was wrong we found ere long.

Though what, we could not tell

We pulled till the sweat drops fell around

As we’d never pulled before.

An hour by the clock, but not one sound

Came down through the bell-loft floor.

On the morrow, all folk of the same thing spoke.

They had stood at the midnight time

On their doorsteps near with a listening ear

But there reached them never a chime.

We then could read the dye of our deed

And we knew we were accurst

But we broke to none the thing we had done

And since then never durst.’

(Winter Words 1927)

By the end of 1927 Hardy was ill and very weak. His wife, Florence, wrote that:

“As the year ended a window in the dressing-room adjoining his bedroom was opened that he might hear the bells as that had always pleased him. But now he said that he could not hear them and did not seem interested.”

Eleven days later he was dead.

Gareth Davies

First published in the Ringing World double issue of 22/29 December 1989